July 15, 1951: on a quiet Sunday morning in an otherwise sleepy farming community, a dry hot wind was kicking up the dust and dry grass as the heat index started to rise. Just outside of town, in the shadow of the iconic Scotts Bluff National Monument, a large group had gathered and a boy of fifteen awaited his fate. It was Soap Box Derby day and this was the last time he’d be racing this course. Next year he’d be too old to compete. If he was ever going to make it to the All-American Soap Box Derby in Akron, Ohio, he’d have to be the last racer standing at the end of the day. He was out of chances and out of time. He’d been here before. As a very young boy he’d watched in awe as the older boys his father sponsored raced their cars down the 1000 foot slightly curved sloping course—hands tight on steering wheels, eyes fixed forward, wheels creaking as they escaped the wooden starting blocks. He was immediately hooked. As soon as he was eligible, at age eleven, he built his own car and entered the competition: in 1947, his first year, he wrecked his car in the first round before getting to the bottom of the hill, in 1948 he was eliminated early on by the ultimate champion, in 1949 he won the prize for the fastest heat of the day but lost out in the semi-finals, and in 1950 he also ran the fastest heat of the day in what he called his “best car” but was defeated in the finals. During the previous Christmas holidays he had started to build what he hoped would be his best racer yet: in his own words he “tried to use the best ideas of my other cars and …tried to eliminate the mistakes…” What he created was a sleek work of art, precision built with interchangeable sides made of laminated cedar with the ends made of pine; all kept together with more than 300 screws and painted shiny black. The boy’s dedication to winning went even further than the countless hours of crafting the perfect racer. Just ten days before Derby day, he realized he was over the allowed (car + driver) weight limit of 250 pounds. At fifteen it was much harder to stay within the limit than it had at twelve and thirteen. He was 9 lbs too heavy. He consulted his doctor and “lived on salads and fruit juices” until the official weigh-in on the Saturday night before race day. By that time he had lost 13 lbs, coming in 4 lbs under the limit. Now 32 competitors from throughout the region stood between the boy and his dream of racing in Akron. He made it through the early rounds only to meet his best friend, Gene Niederhaus—who’d already posted the best time of the day—in the semi-finals. Their race was so close it was deemed a dead heat by the judges. A run-off was necessary to determine who would move on. On the second try he crossed the line three feet ahead of his best friend. He would move on to the finals. Almost three hours after the Derby began a hush settled over the more than 1500 spectators as the boy placed his car in the starting blocks for the final race of the day. His competitor in this ultimate challenge, Tommy Cone, was from up north in the sand hill country. He surely had supporting friends and family in the crowd. But the overwhelming favorite was the 15-year old veteran. His parents, his sister, his uncles, aunts, cousins, even his grandfather stood in the crowd. They knew what he’d been through to get to this final race. And the townspeople knew too thanks to a series of newspaper articles, including one written by the young boy himself and published in the Daily Star-Herald several weeks before. It was no longer just the boy’s heart on the line. To say he was a crowd favorite was an understatement. It’s easy to imagine a collective deep breath as the boy took off down the track for one last time, as the crowd broke out into cheers, shouts, and stomping until they saw their boy cross the finish line first. In his fifth year competing, HE was finally the last one standing. He had earned a ticket to the race of his dreams, the All-American Soap Box Derby championships.

The final race on Derby Day: Dick Otte vs. Tommy Cone. (The man on the far left appears to be Dick’s father Fred, and the woman standing at the very top- on the bed of the truck- looks like his mother Dolly. Standing next to her is likely her brother, the “Schank” in Schank Roofing that appears on the side of Dick’s racer.)

In the weeks that followed he would be celebrated. The mayor of Scottsbluff presented him his official Soap Box Derby championship trophy, news of his exploits would be shared around the state, the Governor of Nebraska would send him a congratulatory card, and his car would go on display at a local business so that everyone could get a first-hand look before it was shipped off to Akron. All of this, of course, would pale in comparison to what he found once he reached Derby Downs in Akron in mid-August. It was a multi-day event filled with parades, a special Derbytown camp, celebratory dinners, and even a ride on a speed boat. Race day would feature 141 competitors from the United States and Canada with a cheering crowd of more than 50,000. The special guests for the ceremonial Oil Can race were (not yet politician) Ronald Reagan, Andy Devine, and ventriloquist Paul Winchell accompanied by Jerry Mahoney. U.S. Air Force Commander General Vandenberg was in the crowd as was the number one Soap Box Derby fan Jimmy Stewart. Stewart narrated a film documentary featuring the 1951 running of the All American Soap Box Derby entitled “Winners All” in which he speaks of what it is to be a successful American (man) and how the Derby epitomizes those values: “being good at what you are,” “learning sportsmanship and fair play,” “measuring our success only in terms of those who come after us,” and “working together for a common goal.” Yes, he intonates, these Soap Box Derby cars might be four-wheeled packages of hopes, dreams, and ambitions—but what they really are is a clearing house of do-it-yourself, ideas-types that make America what it is. “Every one of us wins,” Stewart tells us, “for the strengths of character and purpose that the Derby fosters is the self-same strength that makes a nation.” And while our hometown hero would not make it past the first round on Derby Day, it hardly mattered as his world had been irrevocably expanded. Jimmy Stewart’s words rang true for the boy. He did not race to set the world on fire, but he raced to be the best of who he was. That was the prize he took away from his Derby experience. And perhaps no one really understood how much he took this notion to heart, as it’s really only in the looking back that one can see this boy’s path from the moment of his first crash on the side of a dusty hill to his achievements later in life.

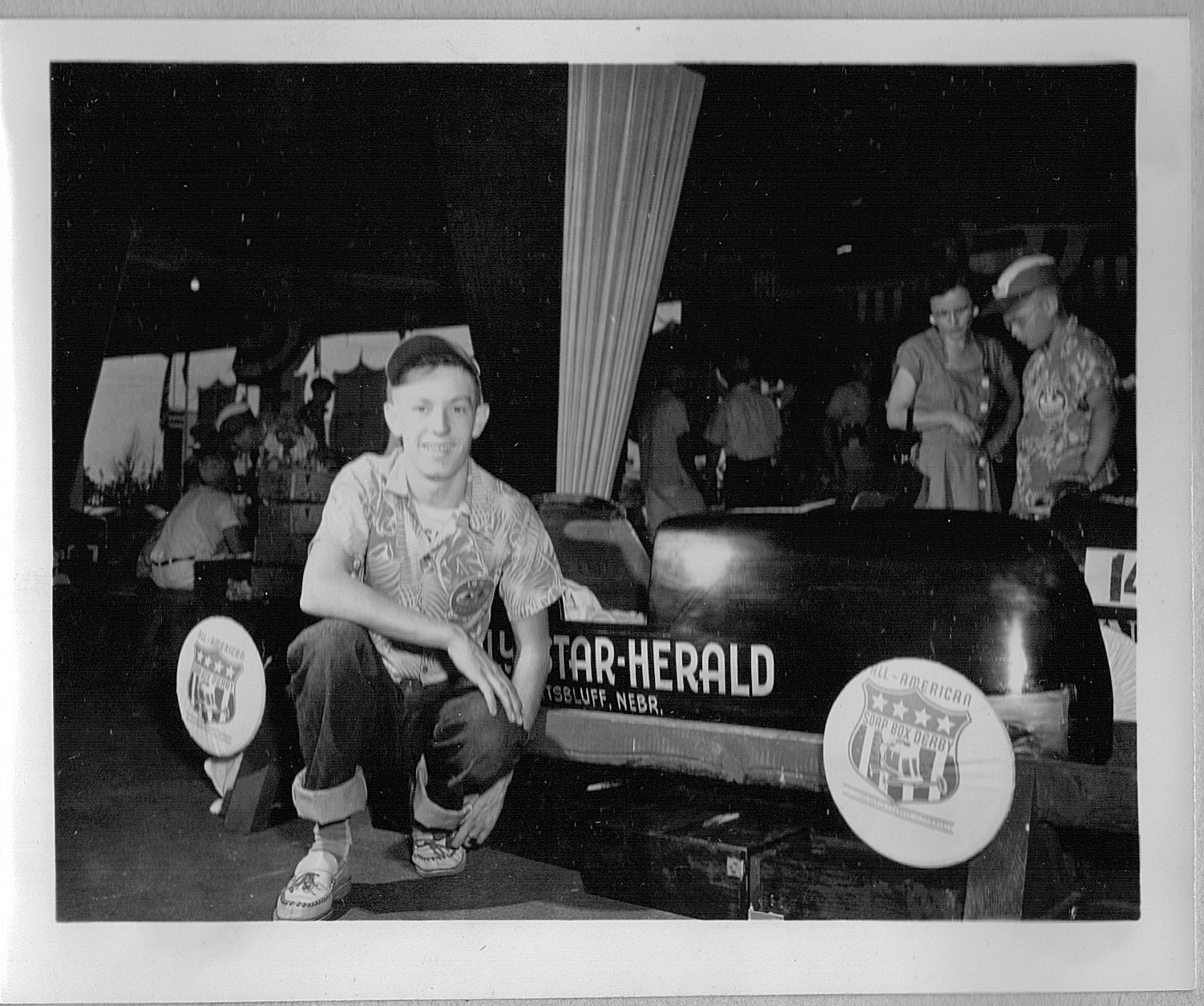

Dick Otte with his car in Akron for the All American Soap Box Derby, August 1951. His Akron sponsor was the Scottsbluff Daily Star-Herald.

Knowing what came after allows us to stretch back in time to identify the places… “HERE is an important moment” or “HERE is a fact that matters”… like shiny little tacks marking spots on a road map. This particular road map—in the form of over-flowing filing cabinets, dusty boxes, and plastic storage containers—was left behind by Dick Otte, the Soap Box Derby boy, who would one day become my father. As it turns out Dick left this earth too early, before he had taken time for any semblance of retrospection or introspection. He was generally not a man who “looked back.” What he did do is “collect” things along the way…scrap books, photos (and related forms such as slides, film, cd’s, and the like), magazine articles, books, personal documents and all manner of ephemera and objects related to his work and interests. These items, collected over sixty plus years, were packed and unpacked, stuffed into drawers or storage containers, or left sealed in packing boxes, as my parents moved back and forth across the country multiple times. Dick gave these things little thought beyond knowing that someday he’d take the time to go through and make sense of it all. And after he died, the items were left untouched. Some combination of the deep sadness of her loss and being overwhelmed by the sheer volume of it all had paralyzed my mother. My sister and I were forbidden to touch these boxes.

Looking back on the road map Dick left behind, it is obvious that his “do-it yourself-ideas-guy” persona came naturally. He was born—in 1936—into a family of pioneers. His paternal grandfather, Henry Otte, arrived in Scottsbluff Nebraska by wagon in 1907 to claim an 80-acre parcel of the American Dream. He lived in a sod house on the flat, treeless plains, developing the land and finally building a tiny 4-room house where Dick’s father Fred was born—the first child born on their new land. Henry would receive his official land patent in 1913, signed by President Woodrow Wilson. Dick’s maternal grandfather, Charlie Schank, arrived in the area during the depression as part of a WPA farm irrigation project, as a member of the Veteran’s Civilian Corp. Charlie was a German Alien who had served the United States during WWI. A stone mason, Charlie would help build a lighthouse on what would become Lake Minatare, a man-made water resource in the middle of the plains. (yes…a land-locked light house…it still exists.)

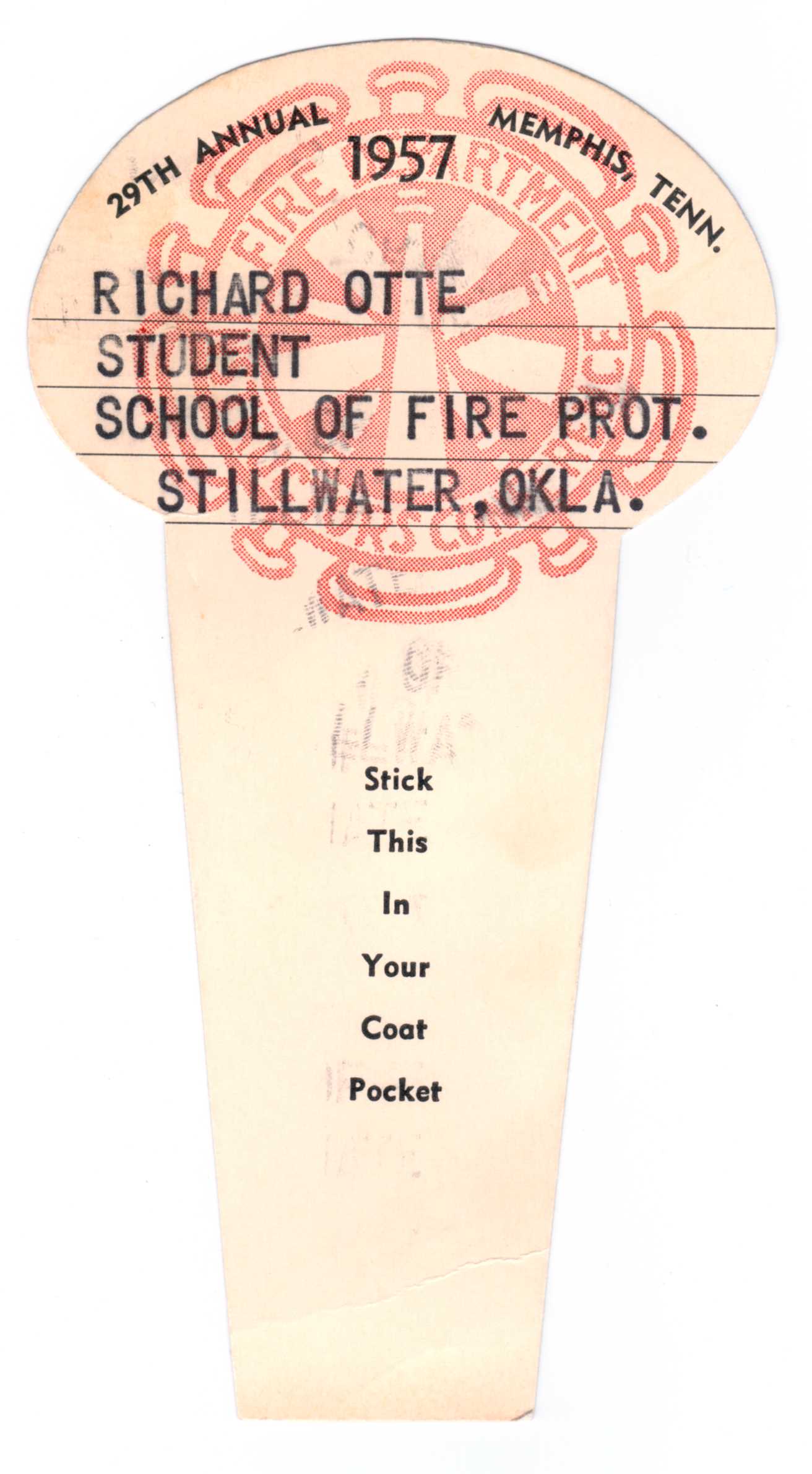

Dick was named after his maternal uncle, Richard Myron Schank, who died five years before his arrival—of internal bleeding from injuries received when a wheel from a car flew off and hit him while he stood watching an auto race at the Nebraska State Fair. My grandmother had no idea what she was doing when she handed my father this legacy. She dreamed of her son the doctor and would never understand the road he would ultimately choose to follow. The biggest influence in Dick’s life was his father Fred, my grandfather, who was the Minatare Fire Chief for twelve years and would serve as a Deputy State Fire Marshall for the State of Nebraska for more than twenty. Overall, Dick grew up surrounded by family who created a life and community out of one of our nation’s most barren landscapes. They built farms and businesses (sometimes literally) from the ground up. After a brief stint in the Coast Guard, Dick attended Oklahoma State University, where he bunked in a firehouse and studied Fire Engineering and Safety. He married, started a family, and held a series of jobs in the Insurance and Fire Service industry—setting up safety programs and selling fire equipment for industrial applications. These were his “day jobs” that would support his new family and set the groundwork for a new world he would soon create.

My father’s livelihood and passions were never a mystery to me, as I lived them first-hand from an early age. I was a lucky daughter. Not only did I soak in my family history, but I was able to watch my father in action throughout my life. One of my earliest memories is being at a racetrack, Riverside International Raceway, where Dick was Safety Director for nine years during the 1960’s (his weekend job). It was here that he would develop the first ever water wall, a specialized fire rescue dune buggy, and in-board fire protection systems for race cars: in general Dick helped to pioneer an industry, all while pulling men out of burning wreckage and keeping the spectators safe. Beyond Riverside he consulted with other raceways such as Atlanta, Michigan International, and Texas International, and worked on special projects for USAC, NHRA, SCCA, and the California Sports Car Club. Before my sixth birthday Dick had created the TRW Safety Caravan, a first-of-its-kind entity that would provide fire and safety services along with specialized training to racetracks. The summer I turned seven my family followed the NHRA drag racing circuit around the US and Canada. One night I sat across the dinner table from a man who held up his bandaged paw in a toast to my father. A freak accident caused this motorcycle racer to have all of the fingers of his right hand cut off as he raced down the speedway, but for the diligence of Dick Otte, who carefully collected each digit from around the track, putting them on ice and driving them to the hospital where they were reattached by a medical team.

My sister Cindy (in back) and me in one of the fire-fighting Dune Buggies after a race at Riverside Raceway circa 1969

From my own collection: my “family day” ID card issued for a visit at the Space Technology Laboratories in Redondo Beach. Fire Suppression Systems on Space Rockets were of primary concern after the Apollo 1 tragedy that year. My memories of a day spent at “Space Park” rival those of TRW’s private family day at Disneyland.

Dick Otte (center in plaid shirt and baseball cap) with one of his early Rescue Crews at Riverside Raceway. In year one he had 3 men and 1 truck, within two years he’d grown it to 75 men and 10 trucks. Soon he would develop specialized equipment like the first ever fire-rescue dune buggy. He’d serve as Safety Director at Riverside for 9 years.

Dick Otte in action at Riverside, putting out the fire on a wrecked racer (c. mid-1960’s)

The arrow is meant to point out the critically injured driver, but it’s a great indicator of Dick Otte working to free said driver. Late ’60’s, early ’70’s at Riverside Raceway

It was Dick’s reputation as an innovator and expert in fire protection and safety rescue within the motor sports industry that brought him to the attention of George Hurst. Their paths would cross often on tracks across the country as George had made his name in the race world with his famous Hurst shifter. George had a new invention he needed help with, a 350+ lb behemoth “tool” that would enable race car drivers to be cut out of wreckage after a crash. The tool, which was pulled around on the back of a pickup truck and first demonstrated at Daytona Motor Speedway, was too heavy and too unwieldy to be effective. Dick started to work with George, offering him advice on how this tool needed to be reengineered to be of real service on a racetrack, where speed was everything. There was something more Dick understood about George’s invention though…it may have been born on the racetrack, but it had applications that reached much further than anything George had in mind. As Supervisor of the Fire Protection and Safety Department of TRW—his official day job at the time—Dick had been working in TRW’s Space Systems Group, helping to develop fire suppression systems for NASA rockets. But it was the conversations he started having with the product managers in the Performance Parts division that had laid the ground-work for the TRW Safety Caravan, with the realization by all involved that bigger engines and more sophisticated parts were leading to faster and faster cars on the racetrack (and on the roads.) Dick knew that any technology developed in the Space Technology or Performance Parts divisions had applications elsewhere. Likewise, George Hurst’s extrication tool would be important beyond the racetrack. George tried to entice Dick into moving east to Hurst headquarters in Warminster, PA to help with this process, but he was busy with his traveling TRW Safety Caravan, and a company he’d purchased called Filler Safety Equipment, where he was developing special driver suits (Shadow Formula I Team 1975-76), as well as fire extinguisher systems for cars used in Lemans, Grand National Stock Cars, and Funny Cars in drag racing.

Dick Otte (front & center with red sneakers) with his TRW Safety Caravan Crew. Notice the Hurst “Jaws of Life” prominently featured (mid-right side)- c.1972

The cover of Speed & Customer Dealer August, 1971- featuring Dick Otte racing towards a drag racer at an NHRA event. The magazine featured an article about Dick and the TRW Safety Caravan

Regardless of his other ventures, Dick believed in George’s invention and understood greatly the implications. If George could figure out how to get this “tool” into a hand-held, one-man version, Dick knew they’d have a product he could sell not just to racetracks, but to the fire service industry across the country. He suggested George talk to one of his former colleagues from Ansul, (the company he had worked for just prior to TRW). It would take some convincing on the behalf of George and Dick, but Mike Brick, was persuaded to take on these reengineering efforts, becoming the first “in-house” employee on this new project. Meanwhile, Dick and George created a new entity, a California corporation called Hurst Life Systems, Inc. which laid the groundwork for a sales and marketing entity, fusing together Dick’s work on the TRW Safety Caravan and Filler Safety Products with what was to come. My dad would continue on his various endeavors and start to pre-sell this new evolving product. The first proto-type of this extrication tool wasn’t available until April 1971. It was this proto-type that would be shipped back and forth across the country for demonstration purposes until the tool went into official production. The first time this tool (not yet called the Jaws of Life) was introduced at a trade show was the spring 1971 SEMA show in California, which featured Dick’s TRW Safety Caravan, driving suits from Filler Safety, appearances by the popular Hurst Shifter-girl Linda Vaughn, AND a dragster. (The Jaws were an official part of the TRW Safety Caravan from this point forward.) This introduction was carefully calculated by Dick to emphasize the responsibility the Auto Manufacturers had in embracing “safety” as they developed faster and faster cars. (This was also the beginning of Dick’s famous trade show booths which often featured the unexpected, from a fast car to Lady Godiva arriving on horseback with live bagpipe players.) While engineering and production were being handled on the East Coast, Dick handled most of the sales and marketing. In his own words, he knocked on any and every door (fire stations etc) and talked to whoever would listen. From track rescue the Hurst tool would be introduced to the fire service community as the ONLY tool available to quickly extricate victims of car crashes. It was all about “speed.” The very first tool delivered was to the Parkland (PA) Fire Department in December 1971. Through time, Dick would end up focusing all his sales, marketing, and product development efforts on Hurst rescue tools. By 1975 he would move his family to the East Coast, near the Hurst headquarters and become the first National Sales Manager for Hurst’s Safety Products Division, building an unparalleled distribution network across the country. It took rival companies with competitive extrication tools years to catch up.

Dick Otte and Mike Brick on the job at Ansul circa 1963…it looks like Mike is wearing a pair of Dick’s overalls if you look at the name badge

The first public introduction of the Jaws of Life (then called the Hurst Power Tool) at the 1971 SEMA trade show in California. Pictured here is Dick Otte (with possible George Hurst’s wife?) The booth featured the TRW Caravan.

Dick Otte and Hurst Shifter Girl Linda Vaughn at the 1971 SEMA show in California. Along with the TRW Safety Caravan & the Jaws of LIfe, the booth featured specialized driving suits developed by Filler Safety Products (and an NHRA Funny Car too).

An early prototype of the Hurst Power Tool (aka Jaws of LIfe) demonstration at Hurst Headquarters in Warrington, PA, circa 1971. Pictured at left is George Hurst.

The Jaws of Life “in action” at an NHRA race event circa 1971-72, notice the driver is still in his “cage” awaiting freedom

It’s difficult to think back to the time when there was no such thing as the Jaws of Life, as the Hurst tool became known. Today “Jaws of Life” is a part of our lexicon. When someone wants to demonstrate the difficulty of getting out of a tight or dicey spot they say “you need the Jaws of Life!” To a first-responder, saying “get me the Jaws” is like saying “hand me a Kleenex.” And despite patent considerations “the Jaws” or “Jaws of Life” is used to describe any extrication tool regardless of who the manufacturer might be (of which there are a number.) But back in the early 1970’s (and prior), if you were injured in a car crash, chances are you would bleed to death before a first-responder could get you out of the wreckage. There were no specialized tools, just things like crowbars, saws, blowtorches, or similar. It could take hours. What George Hurst, Dick Otte, and Mike Brick—along with various other Hurst facilities folk—developed was unprecedented. This extrication tool and its hydraulic power unit could free crash victims in mere minutes. Not hours as before. Yet still, its introduction to the fire service market was not a foregone conclusion. The price was prohibitive for many fire companies and people didn’t quite understand what it did. This is where Dick’s innovative nature really came into play. As it happened there was a new television show, Emergency!, which featured the exploits of two Los Angeles County Fire Department paramedics, John Gage and Roy DeSoto (played by Randolph Mantooth and Kevin Tighe). Dick decided it would be a great idea to get the characters on the show to use the tool, to show its life-saving qualities and ease of use, as he knew fire and emergency personnel across the country were all tuned in. Dick had a friend (ironically named Dick Friend) who was the Public Information Officer for the Los Angeles County Fire Department. Through that Dick he became acquainted with R.A. Cinader, the producer on the television show Emergency! Cinader informed my father that the show would not feature any equipment not already in use by the LA County Fire Department, which prompted Dick to immediately arrange for the department to receive a “present” which arrived in April of 1972. (The arrival of this tool and a subsequent demonstration was featured in the Los Angeles Times on both April 4 and April 5 under the headline “Jaws of Life Can Save Trapped Motorists.”) Once the Hurst tool was “officially” in use by the department, the producer gave the go ahead for its use on the television show. A script was written featuring a little girl trapped in the wreckage of a car after it was mangled by a drunk driver and (of course) the Jaws of Life would be needed to save her. Dick Otte provided training to the actors in the use of the tool and was onsite the day of filming (in June of 1972). The actors were filmed “in action” but in truth, when it came to the close ups of the tool at work, those were Dick’s hands that were in action. My mom, sister, and I were also onsite that day. We watched for hours as they filmed what would become mere minutes at the top of the show. On October 14, 1972 the “Peace Pipe” episode aired to a national audience, showing the “Jaws” in all their glory. (This episode can currently be found on Netflix.)

Dick Otte (in the orange coveralls) teaching actor Randolph Mantooth how the Jaws of Life works on the set of Emergency! in June of 1972

On the set of Emergency (June 1972), Dick Otte inside the “crashed” car setting up for filming

On the set of Emergency! in June 1972: the actors look on as Dick Otte uses the Jaws of Life during filming of the “Peace Pipe” episode

I have heard in recent months claims by certain individuals that it was an actor on the set of Emergency!, through a flubbed line, who gave the Hurst tool it’s “Jaws of Life” nickname. I will state here unequivocally that it is just not true. While the trademark for the name “Jaws of Life” was not officially patented until September 2, 1975, the registration form lists the “first use” as 28 Sept 1971, and the first “commercial use” as 24 January 1972. This Peace Pipe episode was filmed in June 1972. As part of their pre-filming training, the actors were shown a short film Dick had produced early on called Collision Rescue. One of the original Hurst salesmen of that time, Jack Young, recalled the film as “a sales tool disguised as a training film.” The film featured the words “saved from the jaws of death by the Jaws of Life.” This is most likely where the actors would first hear this expression (if they hadn’t read the LA Times articles two months prior!) They did not “invent” it themselves nor was the expression used in the episode in this manner (one of the actors actually says “…let’s use the chains on the Jaws then.”) Dick Otte’s version of how the nickname came about was that a female journalist came upon an accident and witnessed first-hand the tool in action…saving a life. She then utilized the expression “saved from the jaws of death by the Jaws of Life” in an article she wrote about her experience. I have yet to find a copy of that article which I assume was published in late 1971 prior to the filming of Collision Rescue. I was a very impressionable young girl at the time…and it stuck with me that first, a woman wrote about the Hurst tool in the newspaper, and second, that it was a woman who focused on what was essential…the Jaws meant life.

It was during this time, and really the decade to follow, that the Jaws of Life received unprecedented attention in the media. Newspapers and television news stations reported on local demonstrations of the Jaws at work. The article (mentioned previously) that appeared in the Los Angeles Times on April 4, 1972, was typical of the time as it described: “the tool, nicknamed the “Jaws of Life,” can crunch, spread, twist, and tear the frame of a car that has wrapped itself around a passenger during an accident.” And when crash victims were “saved by the Jaws of Life” heart-wrenching articles were written reporting all the details of the rescue (often accompanied by photos). A town that didn’t have the Jaws would call upon one that did and request the use of the Jaws. Newspapers also reported on the fundraising efforts of local citizens who held raffles, bake sales, and various fundraisers in order to purchase the Jaws on behalf of their fire department. It became a source of community pride to purchase a Hurst tool and present it to their fire department. A community could no longer afford NOT to have the Jaws of Life at the ready.

Training the sales and distribution team. Dick Otte (top: at left) and (bottom: in center holding the tool). Training was always serious business, and saving lives was most often a gruesome task, but Dick believed in taking time for fun whenever possible.

Dick would move on from Hurst Safety Products and the Jaws of Life in 1978. It would be more than a decade before he would return to marketing and product development of hydraulic extrication tools when he became president of Code 3 Res Q Inc. in St. Louis, which sold a product manufactured in Holland. In the interim years Dick worked on a number of projects for a number of companies: He marketed fire products for Kidde, LTI, Inc., PemFab, and American Pump (which became American-Godiva during his tenure) and he served as the Deputy Director of the International Association of Fire Chiefs in Washington DC. Throughout he consulted on a number of projects including the SMS “Flying Fire Engine” for McDonald Douglas, FireOut Systems, Ltd., ISFSI (and the Fire Department Instructors Conference -FDIC). He knew the fire service market inside and out: the products, the manufacturers, and the people who used them. He worked with and trained fire service personnel across the country; if a practice or training procedure didn’t exist, he would create it. Dick was one of the originating National Fire Protection Association technical committee members for NFPA 1936 Standard on Powered Rescue Tools, and NFPA 610 Guide for Emergency and Safety Operations at Motorsports Venues.

Throughout, I was lucky to tag along with Dick when I wasn’t in school: When I was 10, I joined my dad on a particular trip making sales calls throughout the Southwest. We visited fire departments in New Mexico and Arizona where he put on demonstrations of the Jaws of Life, trained personnel, and answered questions. During the summer of 1979 we traveled with the NHRA drag racers once again as Dick had developed a tie-in between the LTI ladder towers he was marketing, the hot-cinnamon Jolly Rancher candy “Fire Stix,” and the top fuel dragster driven by John Abbott. I became fast-friends with John’s daughter and we had a great summer culminating with John racing in the finals of the U.S. Nationals in Indianapolis. The summer between my freshman and sophomore years in college he hired me as a photographer, and I found myself back on the racetrack while he was working promotions for Miller Racing (Miller Brewing Company). I traveled with him to several races, taking photos of the action around Miller’s Funny Car driven by Dale Pulde, sold t-shirts, and drove a mini-funny car around the track delivering contraband beer once the races ended. Years later when I was between jobs Dick hired me to sell advertising and work the Fire Department Instructors Conference (FDIC), an annual conference then held in Cincinnati. Whenever schedules allowed I would join Dick at fire service conferences and trade shows—which were always fun to attend—visiting cities across the country and getting reacquainted with the folks who’d been a part of Dick’s life (and mine!) for as long as I could remember. He was a loyal friend and those who’d traveled along with him at various points loved to share their “Dick Otte stories” with his daughter. I loved having these moments when I would see my father in action once again.

Photos I took circa 1974-75 of Dick Otte during “fire house” calls…demonstrating the Jaws of Life on a southwest sales trip

Jaws of Life demonstration circa 1976. (That’s me just beyond my dad’s left shoulder…I tagged along whenever I could.) By this time, very few (if any) had logged as many hours demonstrating and training others on the Jaws as Dick Otte had. He had built a reputation as …”the fastest can opener in the country…”

John Abbott’s Jet-X Top Fuel Dragster. He made it to the finals of the U.S. Nationals at Indianapolis Raceway Park (1979). Between rounds…and hanging out in the truck in our crew shirts… (that’s me on the right!)

In 1993 Dick’s career would come full-circle when he went to work for Curtiss Wright Flight Systems, Power Hawk Team. In the early 1990’s, Bill Hickerson, an employee of Curtiss Wright, developed the first non-hydraulic Jaws-type tool, named the Power Hawk. This technology was a jump forward in the world of extrication tools. The company knew the defense and commercial aerospace markets, but had no experience in the fire service market. Dick was brought in as the Marketing Director and was able to do for Bill & the Power Hawk Team what he had done for George Hurst—bring the next generation extrication system to the fire market. It was officially introduced in 1994 at the Fire Department Instructors Conference (FDIC) in Cincinnati. Introducing a new extrication tool to the fire service was not an easy proposition. But because the Power Hawk did not utilize hydraulic fluid or gasoline-powered hydraulic pumps, it would move into new worlds of urban search and rescue and all manner of “contained” and “collapsible” space rescue—places traditional rescue tools could not go. In effect, it would expand the market—and provide solutions in areas that not everyone even quite understood as potential problems. Never would this fact be more evident than the days that followed the September 11th terrorist attacks. Dick manned the phones day and night as he and his fellow Power Hawk coworkers used every contact and source at their disposal to get Power Hawk Rescue Systems into the hands of the rescue teams on site at Ground Zero and the Pentagon. It all became very personal as they were well aware it was their friends and colleagues who had rushed into those buildings when all hell broke loose. The Power Hawk team had a particularly close working relationship with FDNY Rescue 1. Dennis Amodio (a retired Lieutenant from FDNY Rescue 1) and his best friend Lt. Dennis Mojica were partners in Technical Rescue Services, Inc., sales representatives of Power Hawk rescue systems. On the morning of 9/11 while Amodio was training firefighters at Miami-Dade International Airport, Lt. Mojica was on duty at Rescue 1 in Manhattan. Lt. Mojica—a 30 year veteran of the FDNY and a member of FEMA’s Urban Search and Rescue Team—would spend his last breath saving lives in the North Tower of the World Trade Center before it collapsed. From the moment he heard that the North Tower had collapsed, Dennis Amodio could think of nothing else but getting to NYC and finding his best friend. He got in his car and drove 22 hours straight thru to NYC, arriving at his old fire house, Rescue 1 on 43rd Street. He would learn that 11 of his brothers were missing from Rescue 1—including Lt. Mojica. In the meantime, the Power Hawk team had gotten clearance to deliver rescue units directly to Rescue 1 and also to set up their Urban Search and Rescue trailer near Ground Zero, where they planned to distribute rescue equipment, recharge batteries, repair tools, and be of service to all the search and rescue teams working in and on “the pile.” Dennis Amodio reported back to his friends at Power Hawk that while working on the pile, he couldn’t help but notice all the “other” rescue tools discarded or simply not being used. It was the Power Hawk system, he said, that gave him and his team the ability to operate in remote and tight areas where other hydraulic tools could not; the Power Hawk had essentially adapted to a situation no one had ever quite imagined before. Amodio worked for more than two weeks, day in and day out, eventually locating the bodies of six of his Rescue 1 brothers, including his best friend Lt. Mojica.

Bill Hickerson (Power Hawk inventor), Gary Wan, Dennis Amodia, and Dennis Mojica at a Curtiss-Wright Power Hawk training seminar

Curtiss Wright’s Power Hawk Rescue System- Urban Search and Rescue Support Training Unit. The “next generation” Jaws-type tool could go places no other tool could…the Power Hawk system was officially introduced to the Fire Market at the 1994 FDIC in Cincinnati, Ohio

It was difficult for Dick not to be onsite at Ground Zero, but he promised my mother that he would leave that to the younger generation. He knew his behind-the-scenes work was critical (my mother said he slept with his cell phone for several days), using his long-time contacts to gain needed clearances to get desperately needed equipment to the right people and places during a time when no person or thing was moving anywhere. In the end, Curtiss Wright Power Hawk donated more than $350,000 in equipment to the rescue and recovery efforts at both the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Like many, Dick lost a number of friends on 9/11. But he was able to take some comfort in the fact that a product he had helped bring to the fire service market had made a difference, had performed as he knew it could, had saved lives and brought home the bodies of fallen comrades.

By now you might be wondering why I have been going through my father’s papers after I told you I had been expressly forbidden to do so. That in itself is an interesting story. Back in June of 2012, I wrote a blog post commemorating Dick’s birthday and father’s day, which always fall within days of each other. It was six years after Dick’s death and I was feeling his loss particularly acutely in mid-June. I posted the eulogy I’d given at his memorial service along with photos illustrating the things I’d referenced. Turns out one of those photos caught the eye of an individual who reposted my blog link to the Facebook page of a man named Richard Yokley in September of 2013. Mr. Yokley left a comment on my blog informing me that he was the co-author of a book on the 1970’s television show Emergency! and that he was excited to discover the photograph of Dick teaching actor Randolph Mantooth in the art of using the Jaws of Life. When the book was written Dick’s name had been lost to time…he was simply known as “the Hurst rep.” Mr. Yokley was now able to put a name to the face and as it turns out he and I had the same set of production photos. (Long live social media!) Mr. Yokley himself had been contacted by a curator from the Smithsonian’s American History Museum who—while developing an exhibit on the Jaws of Life—was looking to confirm information he’d been given that the nickname “Jaws of Life” had come from the set of Emergency! As I outlined earlier, this notion was incorrect, so at the urging of Mr. Yokley I reached out directly to this curator to offer up what I knew. Unfortunately, this curator never returned my emails, and by all accounts was not at all interested in what I had to say.

This got me thinking. The Smithsonian is one of our premier historical institutions, and they were being given incorrect information. Furthermore, my information and knowledge was not deemed important enough to warrant a response to my queries. I started looking around to find libraries or archives that housed “history of the fire service” or “history of rescue tools” or anything relating to the former activities of Dick Otte. And what I realized is that other than the memorials that had been printed in industry magazines that listed him as a “pioneer” or “expert” on rescue tools and motor sports safety, Dick’s contributions were being erased from memory. Some “others” are controlling the stories and (re)writing the histories. “Google” Jaws of Life and what you will find is incorrect, or only a partial story at best. Even George Hurst has been written out of that story in some instances and it was his invention! Full disclosure about me, I am a former employee of the nation’s largest non-governmental archives, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, which houses some 600,000 books, pamphlets, serials, and microfilm reels; 20 million manuscripts; and over 300,000 graphics items covering more than 300 years of US History. I have worked on a number of “historical” projects including co-writing a book of historical non-fiction. What I‘ve learned along the way is that history is quite subjective depending on who’s doing the telling and what information is available (and what information was lost to time.) Having that experience, I’ve known for awhile that Dick’s collection of papers, photos, and ephemera serve an important purpose. Sitting undisturbed for all these years has done him an injustice—Dick’s legacy was being lost to the vagaries of historical retelling. I cannot be mad at the Smithsonian curator who got the story wrong because after all, he did not have access to my mother’s basement.

It was TIME to crack open the boxes. Moreover, it was time to find these materials a proper home: a place where they would be correctly processed and catalogued, and made available to the general public, researchers, & historians. The good news is that all of these items will soon have a new home, the Special Collections and University Archives at the Edmon Low Library of Oklahoma State University in Stillwater. Once processed and catalogued, the public and most importantly, the students of the School of Fire Protection and Safety Engineering Technology, will have access to “The Richard Irvan Otte Collection.”

Edmon Low Library at Oklahoma State University: the new home of the Richard Irvan Otte Collection. OSU’s college of Engineering, Architecture, and Technology is home to the nation’s only ABET accredited Fire Protection and Safety Technology program.

I took over my mother’s dining room for weeks as I “repackaged” more than 60 years of collected materials in what will now become the “Richard Irvan Otte Collection” of the Special Collections and University Archives at the Edmon Low Library, Oklahoma State, Stillwater

In preparing these materials for the journey to their new home, I have spent a fair amount of time with them, days and weeks of time actually. As I have minimally reviewed and repackaged things into clean, consistent shipping boxes, I have been through a bit of an emotional journey. As I said, in the looking back it’s been fairly evident where some of the “look here” shiny tacks of “important moments” were pinned. I had good days and bad days. On the good days I relived some great family memories. I remembered why my dad was such a badass. On a bad day I was left feeling bereft at the images and papers that featured crashes, fires, burned up bodies, a vacant look from a person photographed in a horrible moment. And still other days I found myself cursing my father for leaving such a huge and tedious project. Some 39 boxes are ready to be shipped out—an estimated 200+ linear feet of materials. A large collection by archival standards. And now I release these materials forward. It will be left to others to contemplate them and provide proper context. I look forward to hearing their conclusions.

I was excited to come across what is likely Dick’s first Fire Department Instructors Conference badge…his last FDIC conference was in April of 2006…this means he attended for nearly 49 years (I don’t think he missed many years in between!) The Dick Otte Collection at Oklahoma State will include years of conference attendance badges.

UPDATE:

After posting this blog, I was able to talk directly with one of the curators at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. The Institute agreed to remove the incorrect information from their first-person-account webpage and also committed to additional research time for their upcoming road safety exhibit (which includes the Jaws of Life), to enable inclusion of the Richard Irvan Otte Collection materials and to gain a fuller understanding of the other individuals who played a part in this history. I will post another update when I receive further information about a potential exhibit opening date.

Please note: As of June 2016 the Edmon Low Library Special Collections & University Archives has completely processed these records, thanks to Deborah Hull, Kay Bost, and Suzee Price. For further information about Dick, his career, and the projects he was involved in, you can now access a GUIDE to the Richard Irvan Otte Collection (Collection Number 2014-022). Email the archives directly for further information. If you ask nicely, they will email you a PDF of the guide.

Special Acknowledgements:

- Sandi Otte, my mother and the person donating these materials

- Richard Yokely, co-author of Emergency!: Behind the Scene, who started it all!

- Susan Walker, the librarian of the International Fire Service Training Association at Oklahoma State

- David Peters and Mary Larson, Special Collections and University Archives, Edmon Low Library

- Lee Arnold, Director of the Library of The Historical Society of Pennsylvania

- Chuck Force, one of my father’s bunkmates at the college firehouse and longtime family friend

- Chief Charlie Dickinson, retired Deputy Administrator of the United States Fire Administration

- Bill Hickerson, Power Hawk Rescue Systems

- John A. Ackerman, Fire Service Historian and former publisher American Fire Journal (formerly Western Fire Journal)

- And all the “gang” who joined Dick along the way: Jack Young, Andy Dzuryachko, Dave Ferling, John Otte, Lila Gilespie, Bobby Williams, Brian Hendrickson

- Cindy Duncan, my sister…because this is her story too

Thank you all for your stories, encouragement, and support

I really enjoyed our correspondence and great phone call. I am happy that you finally got into that basement so that we all can remember your dad as you do. Glad to have played a small part in this adventure and hope that the Smithsonian comes around to setting ‘their’ record straight.

Richard

LikeLike

You played a LARGE part Richard! I enjoyed getting to know you too! Fingers crossed…it will all proceed as we’ve hoped!

LikeLike

It’s funny, but in reading this story your father and I might have crossed sometime in the early 1970’s. I was Junior High School student in Lansdale, PA hanging around my relatives (who were active members) at the Volunteer Medical Service Corps Building watching the training on Hurst Tool #2, (Around Christmas, 1971) and remember their Jumpsuits very clearly….It was impressive seeing the “Tool” cut apart an Oldsmobile as the members trained to the staccato blast of the two cycle motor powering the “Tool”. I later had a 26 year career with the District of Columbia Fire Department, and worked with “Squadmen” who appeared in a DOT Training Film on Auto Extrication in the mid 1970’s that may have also involved your father, as it prominently featured No.3 Platoon of the DCFD’s Rescue Squad 3. I would be interested if you have any photos of these Training exercises. Thanks, and a great job documenting a man “Behind the Tool”.

LikeLike

Hi Jeff. Thanks for reading the post and commenting. Much appreciated. Yup…Dick never met a jumpsuit he didn’t love…the brighter the better! So nice to hear about “tool #2” -not sure how well that bit is documented. My family donated all of Dick’s photos etc. to Oklahoma State…they are still processing the records (an enormous undertaking) but there will be a Finding Aid available online at some point through the University archives- likely in the coming year. I’m not quite sure what was what, there were a number of photos, slides, videos and the like. Thanks again. I love hearing from folks who crossed paths with my dad 🙂

LikeLike

The man in the white jumpsuit with red collar demonstrating the prototype in 1971 with George

Hurst is James Hobbins who invented the original jaws of life. Hurst saw a family burn to death in a car accident on his way to work. He told my father he wished you could open a car like a can.

The idea was to introduce it for exposure to the racing world and to eventually use it as a standard for rescue teams. the original prototype weighed 60 lbs. A self taught engineer with over 250 patents in his name including this one with George Hurst. Other items include The

Hurst dual/gate shifter, the roll control, the reverse loc out , Hurst mag wheels, Hurst/Gabriel air

shock absorbers. Trans linkage for Summers Brothers Hurst Goldenrod lands speed record

hold. Check out j.f.hobbins jaws of life.com He worked for Hurst for 17 years from the early 60s to the late 70s

LikeLike

Thanks for the info James. I assumed that man was the original engineer but did not have a name. I am assuming from the name it is your father. When I get a chance I will update the photo to include his name as well. Your father’s contributions should obviously be a part of the Smithsonian exhibit as well. It is exactly what I told the curator, the story of the Jaws includes many people…and he needs to dig deeper as I know he didn’t have this name either. I can email him and give him your link. One day all the pieces of the story will come together as they should. Thanks for reaching out.

LikeLike

These two related Hurst blog posts sure have done a lot of good. You never realized that a Fathers Day tribute would have done so much.

LikeLike

life is strange that way Richard! Thanks for all your help too!

LikeLike